The context

The latest Joseph Rowntree Foundation report — Destitution in the UK 2023 — makes clear what many of us engaged in the charity sector know all too well: there’s been a sharp increase in people living in poverty and destitution in the UK. One headline statistic shows that more than a million children found themselves living in destitution last year. That’s 8.15% of all children in the UK — a shocking statistic that has increased 186% in the last five years.

This topic is front of mind at SoGood due to our ongoing work with St Vincent de Paul — a 300 year-old international charity that aims to help those most in need in our society. It’s led us to look deeper at the state of poverty in the UK — and the apparent increase in the issue’s complexity — so we can tailor our solutions for maximum impact. We’ve dug deep into the research — analysing the state of play in the UK, the drivers of destitution and the viable solutions.

The state of poverty in the UK

Some notes on our research

We’ve taken data from a range of sources but have mostly relied on the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, as we consider them best to represent multiple views and operate without bias. For reference, the research orgs and sources we’ve relied upon are:

The multiple data sources make deriving consistent time series data challenging. We’ve therefore decided that we’re happy to work in general numbers rather than specific time frames. We think the sheer scale of the problem validates this approach. We’re talking here about millions of people living in poverty – so we can take comfort in the fact that whatever we can do to alleviate the problem will have a massive impact.

Research methodologies can vary and definitions are inconsistent. Almost all data is derived from qualitative research, which relies on representative samples. Plus, reporting standards and data capture change over time.

Our aim for conducting this research is simply the acknowledgement of the scale and nature of the issues faced. Given our current UK focus, we’ve stayed away from cross-border comparisons. Our aim is to understand the root causes of UK poverty and destitution so that we can contribute meaningful solutions that offer genuine support without bias.

What our research has told us

An increasing number of people are living in poverty

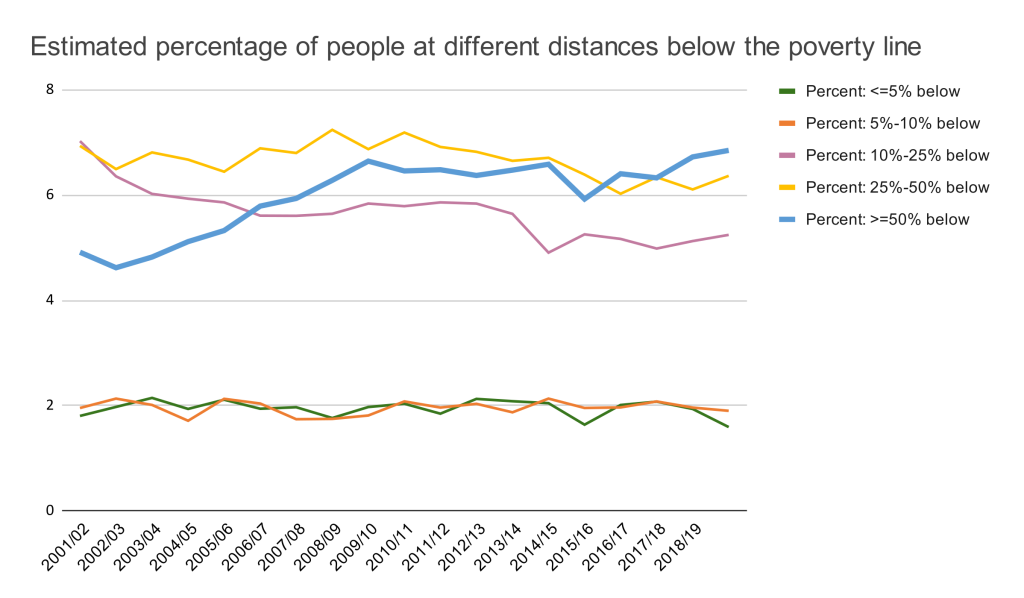

This much is hard to refute. Based on several sources (the UK Government Family Resources Survey (FRS), the HBAI dataset (1998/99–2018/19), and the analysis carried out by The Social Metrics Commission (SMC)) poverty relative to the population has remained constant around 21.5% since 2002. This statistic, however, hides the fact that the proportion of the population over 50% below the poverty line has grown by 2% from 4.9% to 6.6%. This translates to 1.7 million more people finding themselves in destitution over the last 20 years. The chart below illustrates this trend.

Poverty rates are increasing in multi-person households

In JRF’s Destitution in the UK 2020 report, 1,062,000 households experienced destitution – accounting for 2,388,000 individuals of which 550,000 were children. In relative terms, this meant that, on average, destitution affected 1.97 people per household. JRF’s latest 2023 report tells us that those numbers have increased to 1,766,900 households and 3,848,400 individuals. That’s an average of 2.18 people per household.

Our takeaway is that destitution is migrating from single person or couple households to larger family units – and is probably why there’s been such an increase in affected children. Working family households with low incomes are experiencing hardship where none existed before. Family units and lone-parent households that were previously making ends meet are finding it impossible to feed themselves and stay warm, dry and clean. In short, it’s a national embarrassment that’s undermining the fabric of our society.

Immigration is not the root cause

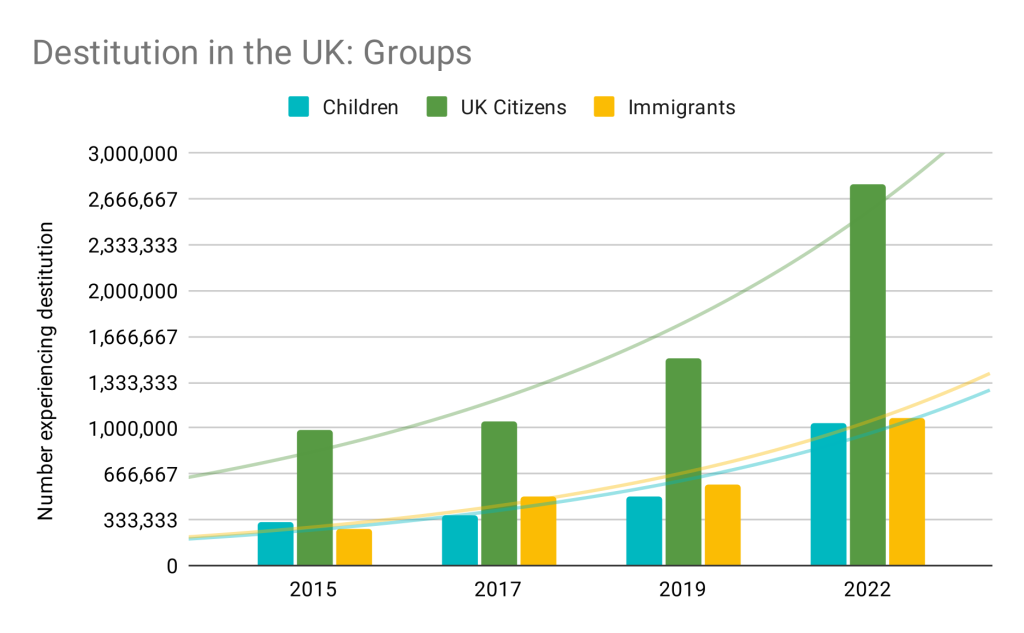

The media generally picks on two categories to tap into emotional reactions and reader engagement. One is the plight of children; the other is the perceived detrimental effect that immigration (and, by association, refugees) are having on the population. Populist media often alludes to the root causes of poverty lying in the increase of legal – and illegal – immigration. The impact of “small boats” which take up countless column inches and attract millions of clicks is certainly a contributor to the figures. The table below breaks the data down by category.

It’s interesting to note that the numbers of immigrants suffering destitution has largely mirrored that of children. The impact of illegal immigration on poverty and destitution is multi-faceted, dependent on numerous factors. Those range from government policies and broader economic conditions, to the circumstances of individual immigrants. Then there are the challenges associated with undocumented immigration – where people don’t have national insurance numbers and therefore cannot unlock minimum state benefits. Our reading of the data tells us that we need to look behind the news headlines. The problem is not simply related to immigration – it runs much deeper in our society than that.

Understanding the complexities of poverty

In order to identify pathways for leading people out of poverty, it makes sense to break down the key factors contributing towards it. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation uses the term “complex needs” to refer to multiple interconnected difficulties that individuals or households may face.

These difficulties often make accessing and benefitting from support services or opportunities far more challenging. Complex needs can vary widely, but they typically include several of the following elements:

- Economic Deprivation: This includes low income, underemployment, or financial instability that can contribute to poverty.

- Poor Health: Health issues, both physical and mental, can be a significant component of complex needs, with individuals requiring access to healthcare and support services.

- Housing Instability: People with complex needs may experience homelessness, inadequate housing, or frequent housing moves.

- Addiction and Substance Abuse: Substance abuse issues can complicate an individual’s own situation and increase their vulnerability and insecurity.

- Social Isolation: A lack of social support networks and social isolation can contribute to complex needs.

- Limited Education and Skills: Limited access to education or skills training can hinder individuals from achieving their potential and breaking the cycle of poverty.

- Legal and Criminal Justice Issues: Involvement with the criminal justice system or legal issues can exacerbate complex needs.

- Domestic Violence and Abuse: Individuals experiencing domestic violence or abuse may have complex needs related to safety, security and well-being.

- Family and Caregiver Responsibilities: Caring for dependents or family members with complex needs can create a set of additional challenges.

- Discrimination and Marginalisation: Discrimination based on race, gender, disability, or other factors can compound an individual’s complex needs.

The problem: charity services working in silos

The entire concept of complex needs recognises that individuals facing multiple challenges are likely to require tailored and multifaceted support services. It therefore stands to reason that these services should consider the interplay between various difficulties and address them holistically.

And this is where the problem lies: in this context, the charity sector has traditionally operated in silos, with minimal access to the sorts of digital collaboration or communication tools that are common to the private sector.

The solution: digital innovation and collaboration

One of the key recommendations from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation that stuck with us is this:

”Local authorities, charities, independent funders and housing providers should also work together to prevent destitution and homelessness for people with restricted entitlement.”

In our view, what’s needed is increased collaboration and coordination across the public sector and charity sector (aka, the Third Sector). That’s what we at SoGood are looking to do. Our work recognises that complex needs require joined-up solutions to alleviate poverty, social disadvantage and destitution across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

To that end, we’re developing tools and technologies that surface and standardise underlying operational data, aggregate perspectives and facilitate the allocation of support in a cost-effective and timely manner.